Oannes: The Advanced Amphibian Beings In Ancient Iraq

Mermaids, enigmatic half-fish, half-human entities, appear in many myths. As deities or spirits, they were adored or feared by many cultures. The majority of them have been female, thus the moniker mermaids. Their male equivalents occur in folklore less frequently, although there were a few. Oannes, one of them, actually precedes the earliest known mermaid – Atargatis, the Assyrian deity – by thousands of years.

The world’s earliest academically validated, fully functional civilizations, Babylon, Sumer, and Akkadia, arose in ancient Mesopotamia. These civilizations lived in what is now modern-day Iraq and Iran, in the midst of a region known as the Fertile Crescent.

These peoples are responsible for the development of writing and the wheel, as well as other critical human advances. The most perplexing aspect of these civilizations’ development is their nearly instant shift from hunter-gatherers to advanced city building civilizations. Their origins remain a mystery. Through their own records and writings, the Sumer tell us that Aliens assisted them in establishing themselves as a viable, intelligent civilization.

Their gods were known as the “Anunnaki” which translates as “Those who came from heaven to earth.” Berossus, Babylonian 4th-3rd-century priest-chronicler described how an amphibian named Oannes came from the Persian Gulf and taught the Sumerians all the advance knowledge needed for a civilized living.

Who was Oannes?

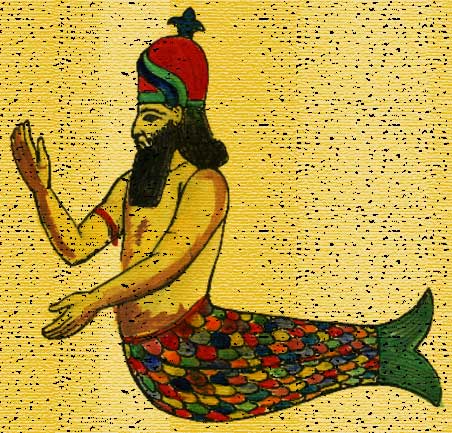

Oannes, also known as Adapa and Uanna, was a 4th century BCE Babylonian deity. Everyday, he was said to emerge from the sea as a fish-human creature to impart his knowledge with the inhabitants of the Persian Gulf. During the day, he taught them written language, the arts, arithmetic, medicine, astronomy, politics, ethics, and law, covering all the needs for civilised living then returned to the sea at night.

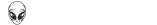

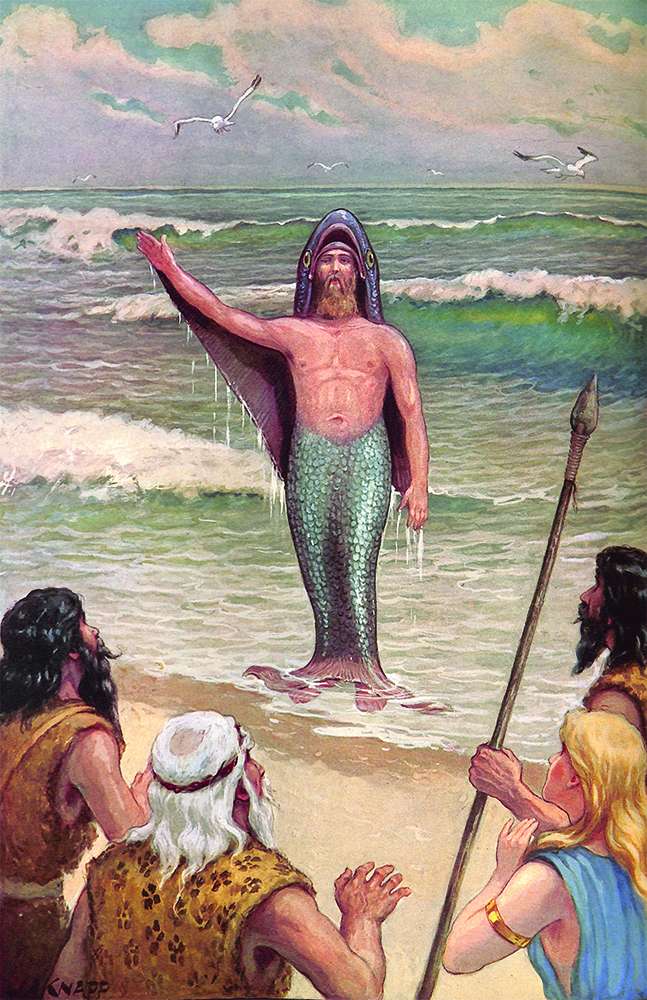

Prior to his intervention, the Sumerians ‘were like animals in the field, with no order or law.’ Oannes did not necessarily look like how we might picture a merman. Some artwork shows him to have a torso and fish tail, but other materials (including carvings) show a human body resembled that of a fish; and it had another head beneath the fish’s head, as well as feet below that were identical to those of a man, subjoined to the fish’s tail. You could almost say it looked like a giant fish ‘costume’.

His voice, like his language, was eloquent and human; and a representation of him has survived to this day. When the sun went down, it was this being’s routine to dive back into the water and spend the night there, for he was amphibious.

Whatever Oannes was, it is undeniable that he was great at what he did. Sumerian astronomers were so brilliant that their estimates for moon rotation are just 0.4 off from contemporary computerised calculations.

They also recognised that planets rotate around the sun, which renaissance science would not postulate until thousands of years. Sumerian mathematicians were also gifted almost beyond belief for their time.

A tablet found in the Kuynjik hills had a 15-digit number–195,955,200,000,000. Mathematicians in ancient Greece’s golden period could only count no farther than 10,000.

We know of Oannes mainly through the stories of Berossus. Only fragments of his writings survived, so the tale of Oannes has been handed down mainly through the summaries of his writings by Greek historians. One fragment reads:

At first they led a somewhat wretched existence and lived without rule after the manner of beasts. But, in the first year after the flood appeared an animal endowed with human reason, named Oannes, who rose from out of the Erythian Sea, at the point where it borders Babylonia.

He had the whole body of a fish, but above his fish’s head he had another head which was that of a man, and human feet emerged from beneath his fish’s tail. He had a human voice, and an image of him is preserved unto this day.

He passed the day in the midst of men without taking food; he taught them the use of letters, sciences and arts of all kinds. He taught them to construct cities, to found temples, to compile laws, and explained to them the principles of geometrical knowledge.

He made them distinguish the seeds of the earth, and showed them how to collect the fruits; in short he instructed them in everything which could tend to soften human manners and humanize their laws.

From that time nothing material has been added by way of improvement to his instructions. And when the sun set, this being Oannes, retired again into the sea, for he was amphibious.

The names of Oannes and the other six sages of civilization – the Apkallu – are inscribed on a Babylonian tablet discovered in Uruk, Sumer’s ancient capital (today the city of Warka in Iraq).

What are we to make of the tale of Oannes?

Is it conceivable that the myth of Oannes the mermaid has some truth to it? Could the mysterious figure who appeared from the sea onto the Babylonian coast thousands of years ago to enlighten mankind and deliver civilisation to the globe have truly existed?

Or was Oannes, the all-knowing man-god in fish form, a means for Berossus to explain the enigmatic origins of civilization in terms that his contemporaries could understand?

We have the notion of a merman/mermaid aiding humanity and being revered yet again, therefore it is reasonable to infer that the relationship with many other mermaid tales is not a coincidence. We can only hope that additional texts about Oannes are discovered because his story continues to entice us to this day!