Tooth Fossils Fill The 6 Million Year Old Gap In Primate Evolution

Researchers have used fossilized teeth found near Lake Turkana in northwest Kenya to identify a new monkey species—a discovery that helps fill a 6-million-year gap in primate evolution.

UNLV geoscientist Terry Spell and former master’s student Dawn Reynoso were part of the international research team that discovered the species that lived 22 million years ago. Understanding the evolution of Old World monkeys is essential because, along with the great apes and humans, they belong to the anthropoid group of primates—primates that resemble humans.

According to Spell, the monkey fossil discovery grew out of a more extensive study of a section of sedimentary rocks in Kenya that contain many different types of fossils, including several hundred mammals and reptile jaws, limbs, and teeth.

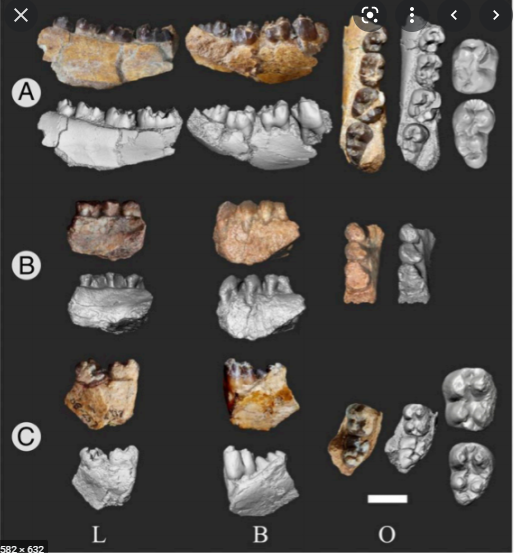

Previous studies had documented the early evolution of Old World monkeys using fossils dated at 19 million and 25 million years old, leaving a 6-million-year gap in the earliest record. However, the new fossil was determined to be 22 million years in age. Isotopic ages on the rocks were obtained in the Nevada Isotope Geochronology Laboratory on the UNLV campus.

“This adds to our understanding of the earliest evolutionary history of Old World monkeys, including changes in their diet with time to include more leaves,” Spell said. “Monkeys originated at a time in the past when Africa and Arabia were together as an island continent. Plate tectonic motions pushed this landmass into the Eurasian landmass 20 to 24 million years ago, and an exchange of animals and plants occurred. It is unclear if competition with newly introduced species or changing climate conditions drove changes in diet.”

Scientists named the newly discovered monkey species Alopecia (“without lots”) due to the lack of molar crests on its teeth. This phenomenon sets them apart from geologically younger monkey fossils.

Old World monkeys are the most successful living superfamily of nonhuman primates with a geographic distribution surpassed only by humans. The group occupies a broad spectrum of land-to-tree habitats and has a diverse range of diets. They evolved to develop a signature dental feature—having two molar crests—which allows them to process a wide range of food types found in the varying environments of Africa and Asia.

“Primitive Old World monkey from the earliest Miocene of Kenya and the evolution of cercopithecoid lophodont” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.