A 500-Year-Old Aztec Tower of Human Skulls Is Even More Terrifyingly Humongous Than Previously Thought, Archaeologists Find

Archaeologists excavating a famed Aztec “tower of skulls” in Mexico City have uncovered a new section featuring 119 human skulls.

The find brings the total number of skulls featured in the late 15th-century structure, known as Huey Tzompantli, to more than 600, reports Hollie Silverman for CNN.

The tower, first discovered five years ago by archaeologists with Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), is believed to be one of seven that once stood in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán.

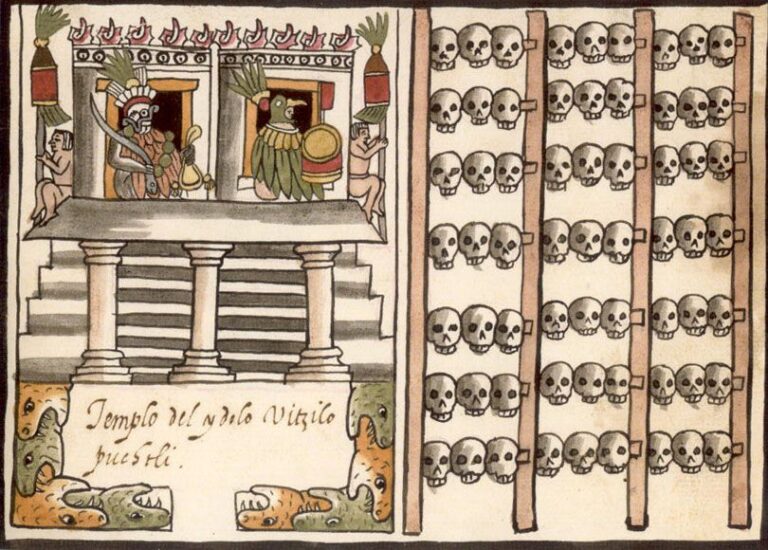

It’s located near the Templo mayor’s ruins, a 14th- and 15th-century religious center dedicated to the war god Huitzilopochtli and the rain god Tlaloc.

Found in the eastern section of the tower, the new skulls include at least three children’s craniums. Archaeologists identified the remains based on their size and the development of their teeth.

Researchers had previously thought that the skulls in the structure belonged to defeated male warriors, but recent analysis suggests that some belonged to women and children, as Reuters reported in 2017.

“Although we cannot determine how many of these individuals were warriors, perhaps some were captives destined for sacrificial ceremonies,” says archaeologist Barrera Rodríguez in an INAH statement.

“We do know that they were all made sacred. That is, they were turned into gifts for the gods or even personifications of the deities themselves, for which they were dressed and treated as such.”

As J. Weston Phippen wrote for the Atlantic in 2017, the Aztecs displayed victims’ skulls in smaller racks around Tenochtitlán before transferring them to the larger Huey Tzompantli structure. Bonded together with lime, the bones were organized into a “large inner-circle that raise[d] and widen[ed] in a succession of rings.”

While the tower may seem horrible to modern eyes, INAH notes that Mesoamericans viewed the ritual sacrifice that produced it as a means of keeping the gods alive and preventing the destruction of the universe.

“This vision, incomprehensible to our belief system, makes the Huey Tzompantli a building of life rather than death,” the statement says.

Archaeologists say the tower—which measures approximately 16.4 feet in diameter—was built in three stages, likely dating to the Tlatoani Ahuízotl government, between 1486 and 1502. Ahuízotl, the eighth king of the Aztecs, led the empire in conquering parts of modern-day Guatemala and areas along the Gulf of Mexico.

During his reign, the Aztecs’ territory reached its largest size yet, with Tenochtitlán also growing significantly. Ahuízotl built the great temple of Malinalco, added a new aqueduct to serve the city, and instituted a strong bureaucracy. Accounts describe the sacrifice of as many as 20,000 prisoners of war during the dedication of the new temple in 1487, though that number is disputed.

Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Andrés de Tapia described the Aztecs’ skull racks in writings about their conquest of the region. As J. Francisco De Anda Corral reported for El Economista in 2017, de Tapia said the Aztecs placed tens of thousands of skulls “on a huge theater made of lime and stone, and on the steps of it were many heads of the dead stuck in the lime with the teeth facing outward.”

Per the statement, Spanish invaders and their Indigenous allies destroyed parts of the towers when they occupied Tenochtitlán in the 1500s, scattering the structures’ fragments across the area.

Researchers first discovered the macabre monument in 2015, when they were restoring a building constructed on the site of the Aztec capital, according to BBC News.

The cylindrical rack of skulls is located near the Metropolitan Cathedral, built over the ruins of the Templo Mayor between the 16th and 19th centuries.

“At every step, the Templo Mayor continues to surprise us,” says Mexican Culture Minister Alejandra Frausto in the statement. “The Huey Tzompantli is, without a doubt, one of the most impressive archaeological finds in our country in recent years.”

Sources: ancient-archeology.com