Stone Age Wooden Snake ‘Staff’ Found In Finland

A 4,400year-old life-size wooden snake unearthed in Finland might have been a Stone Age shaman’s staff used in “magical” ceremonies, according to research published Monday.

With a snake-like head and gaping mouth, the realistic sculpture is 21 inches long and roughly an inch thick at its widest point. A single piece of wood was used to carve it.

It was discovered at Järvensuo, some 75 miles northwest of Helsinki, under a buried layer of peat at an ancient wetland site that scientists believe was occupied by Neolithic (late Stone Age) peoples 4,000 to 6,000 years ago.

It’s unlike anything else that’s ever been discovered in Finland, however, a few stylized snake figures have been discovered at Neolithic archaeological sites in the eastern Baltic area and Russia.

In an email, University of Turku archaeologist Satu Koivisto remarked, “They don’t resemble a genuine snake, like this one.” “Last summer, a coworker discovered it in one of our trenches….” “I believed she was joking, but the sight of the snake’s head gave me the creeps.”

“I used to despise live snakes, but following this revelation, I’ve grown to appreciate them,” she continued.

The study on the wooden snake, published in the journal Antiquity, was co-authored by Koivisto and her colleague Antti Lahelma, an archaeologist at the University of Helsinki.

They believe it was a shaman’s staff used in apparently magical ceremonies by a shaman – someone who similarly connected with spirits to traditional Native American lore’s “medicine people.”

The ancient peoples of this region are said to have practiced shamanic beliefs, in which the natural world is inhabited by a plethora of typically invisible supernatural spirits or ghosts. This traditional concept still exists in Scandinavia’s extreme northern regions, Europe, and Asia today.

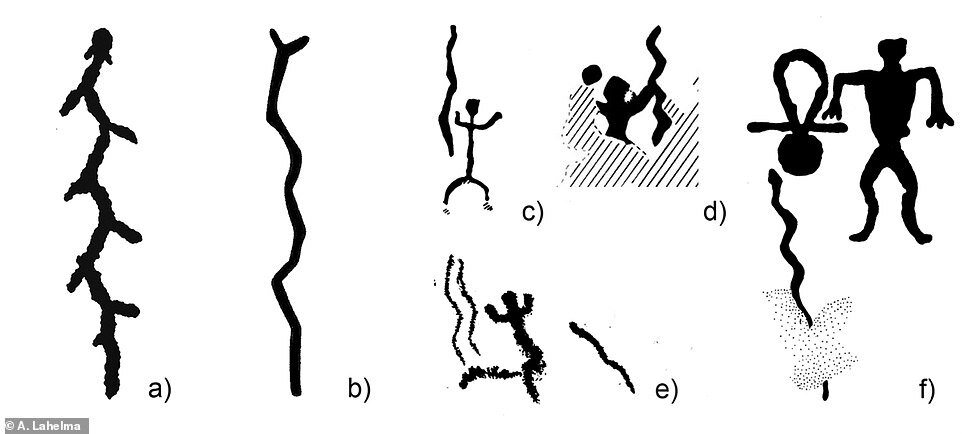

Human figures with what appear to be snakes in their hands are seen in ancient rock art from Finland and northern Russia. They are assumed to represent depictions of shamans clutching ceremonial staffs of wood fashioned to look like snakes. Snakes, according to Lahelma, are highly revered in the region.

“It appears that snakes and people have a relationship,” Lahelma told Antiquity. “This reminds me of ancient northern shamanism, when snakes had a specific role as shaman’s spirit-helper animals… Despite the enormous time difference, the prospect of some type of continuity is tantalizing: Do we have a Stone Age shaman’s staff?” ”

Järvensuo’s figure looks very much like a genuine snake. Two sinuously carved bends define its slim body, a tapering tail. The gaping mouth on the flat, angular cranium adds to the realism. It resembles a grass snake or European adder crawling or swimming away, according to Koivisto and Lahelma. The researchers concluded that the location where it was discovered was most likely a beautiful water meadow when it was “lost, thrown, or purposely put.”

When wood is exposed to oxygen in the air or water, it rots away, but sediments at the bottoms of swamps, rivers, and lakes may hide some organic materials and keep them alive for thousands of years.

When it was occupied by groups of humans in the late Stone Age, the location near Järvensuo is assumed to have been on the shores of a small lake. According to Koivisto, archaeologists have been able to compile a more thorough record of the site because of recent excavations, which have unearthed a treasure of organic remains. A wooden tool with a bear-shaped handle, wooden paddles, and fishnet floats made of pine and birch bark have all been discovered

“What such a fantastic thing,” said Peter Rowley-Conwy, an archaeologist and professor emeritus at Durham University in the Uk who was not involved in the study. “The ‘head’ looks to have been cut to a specific form.”

But he was hesitant to give it further significance, writing in an email, “A skeptic may ask if the sinuous shape was planned, or an unintended byproduct of four millennia of waterlogging.” “I’ve worked with preserved wood on several bog sites, and wood fragments may be rather deformed.”

As many wetland archaeological sites dry up, Koivisto cautions that items like the “snake staff” may be lost.

“Wetlands are more essential to us than ever before,” she added, “because of their susceptibility and deterioration of sensitive organic data sources [due to] draining, land use, and global warming.”