Archaeologists Just Found A 5,300-Year-Old Skull With Evidence Of The Earliest Known Ear Surgery

Archaeologists uncovered the human remains of more than 100 persons when they unearthed the Dolmen of El Pendón in 2016. The dig site in Burgos, Spain, was utilized as a funeral chamber as far back as the fourth millennium B.C.E., according to radiocarbon dating.

However, it would take until now for experts to unlock the secrets of one unusual set of remains — a 5,300year-old skull that contains evidence of the world’s first ear surgery.

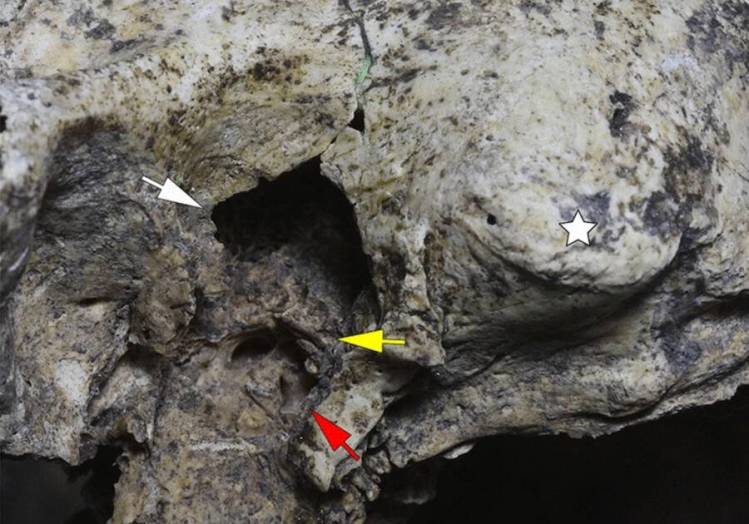

The fractured skull was initially placed in storage with the rest of the discoveries. When researchers examined it more closely in July 2018, they discovered it belonged to a lady who was likely between the ages of 35 and 50 at the time. The presence of two incisions on each side of the skull around the ear was even more astonishing.

“These pieces of evidence suggest to a mastoidectomy, a surgical technique likely conducted to ameliorate the agony this prehistoric individual may have endured as a result of otitis media and mastoiditis,” according to a study just published in Scientific Reports.

In other words, the woman had an ear infection, and the contaminated tissue was removed by drilling into her skull. According to the authors, “given the chronology of this dolmen, this find would be the first surgical ear intervention in the history of mankind.”

The team, which included experts from the University of Valladolid in Spain and the Spanish National Research Center in Italy, ascertained that the presence of bone regrowth around the holes indicated that the patient had miraculously survived her excruciating surgery, which was conducted with primitive stone tools and would have been painful.

A skilled individual made seven cut marks near the left ear canal, indicating that they were made by a trained individual. According to Phys, the treatment is strikingly similar to today’s ear surgeries, which are used to clear the infection from the inner ear. Failure might cause blindness or even death.

“What we can conclude is that select individuals would have achieved a degree of anatomical knowledge and experience as ‘healers,’ or budding physicians, to succeed in this form of primitive healing,” said Manuel Rojo-Guerra of the University of Valladolid’s Department of Prehistory and Archaeology.

Rojo-Guerra and his colleagues determined that the patient was a woman based on the density of her skull and that she was “aged” for Neolithic times based on the loss of her teeth. Her bone regrowth indicated she died within weeks of suspected infection, indicating that the surgery failed to prevent infection.

“For the time, it’s an elderly woman, between 35 and 50 years old, with two bilateral perforations compatible with two mastoidectomies,” he explained. “The presence of these two types of structures in the microscopic preparation enables us to ensure that the woman survived the surgical intervention for at least one month.”

While it’s unclear whether both incisions on each mastoid bone were done at the same time, the procedure would have been excruciating. Before engaging in “progressive circular and abrasive drilling producing terrible pain under normal conditions,” the surgeon most likely recognized the infection with their own eyes.

In the end, the earache she intended to alleviate may have been insignificant in comparison to the treatment. Nearby in the tomb, researchers discovered a flint blade with remnants of sliced bone on its edge and signs of being heated to between 300 and 350 degrees Fahrenheit. They suspect the surgeon used it to cauterize or bore into the bone.

Archaeologists believe that multiple people would have had to restrain her for her to survive the surgery, or that she may have used mood-altering drugs to get through it.

The Dolmen of El Pendón is a multi-phase, single-chamber tomb that was used in burial ceremonies for 800 years, from 3800 to 3000 B.C. Rojo-Guerra and his colleagues Sonia Daz-Navarro and Cristina Tejedor-Rodrguez have been excavating this site for six years and have no plans to stop.

According to The Daily Mail, the location has been used in a variety of ways over the centuries as a ritualistic center. Before it became a commemorative monument, it served as a “complex symbolic and ritual world” for residents in the area, according to researchers.

Finally, evidence of humankind’s earliest ear treatment could be paving the way for more discoveries at the location.